Today’s outline

- LT Fundamental Holds

- Financial and Physical Risks

- Industry Capital Deficit

- Volatility Trap

- Wrong Risk

- Closed Ideas

This week Posts

- New Entries - Trading Diary

- 🇧🇷 Fading Momentum🔻, Yellow flag for neobanks

- Model Update - Stone, Sinqia

- Pix Handbook - Part II

Feedback

Giro’s Newsletter takes feedback very seriously. Therefore, you can always reach out to leave a comment and/or write suggestions.

LT Fundamental Holds

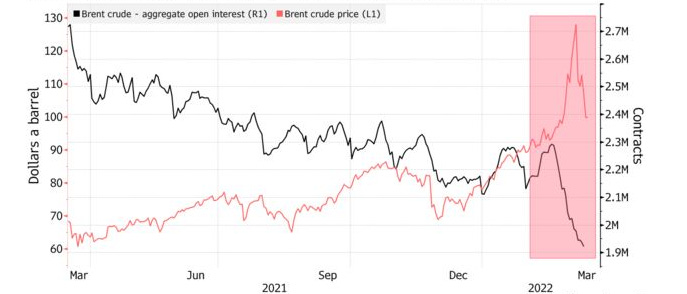

A few weeks ago, Brent prices retreated to below $100/bbl, having shed more than $30/bbl in less than a week.

Oil’s rally sharply turned around amid a resumption of Russian seaborne oil flows, renewed hopes of an Iran nuclear deal, and a resurgence of Covid lockdowns in China, which hit the oil demand.

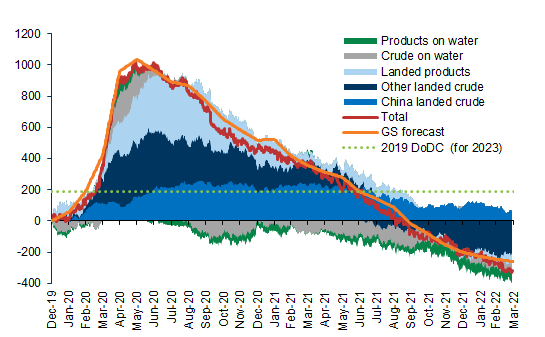

Consequently, global tradeable commodity inventories remained stable amid historical price volatility and inflationary pressures in the past weeks.

According to Natasha Kaneva from JPM:

“This is particularly notable for global tradeable inventories (Ex-China), where the April z-score of -1.36 or -36% below the sample mean was a relative improvement from -41% in March. At this point, it is difficult to discern whether this is indicative of larger inventory builds in Russia and Ukraine due to trade constraints, an early indication of demand destruction or a combination of factors.”

Nevertheless, even considering a moderation for consensus GDP forecasts, the market is trading even tighter than it was before the war considering that:

- Consensus is overly pessimistic for non-jet fuel demand, considering full-year demand below the annualized 4Q21 demand (which happened in 20% of the previous 15 years);

- Recent data shows that the market is operating at a supply/demand deficit, suggesting that demand might be running above the expected;

- Although softening GDP hits fuel consumption, mobility indicators show that driving is pointing to a steeper recovery.

Also, the US administration has confirmed a record large Strategic Petroleum Reserve (“SPR”) release of 180m bbl over the next six months, with the potential for other countries to release 30m to 50m bbl — ~1.2m bbl per day.

However, a release of inventories is not a constant supply source for the coming years, although it might accommodate Brent’s price in the following weeks.

In fact, lower prices in 2022 support oil demand while slowing the acceleration in shale production, leaving, for now, a deficit in 2023 with an eventual need to refill the SPR.

Upsides risks have not been resolved with today’s release:

- Potential logistical bottlenecks to such an unprecedentedly large and long US SPR discharge could reduce its flow rate, with possible congestion on the Gulf Coast in getting to refiners or export terminals.

- The risks of slower shale growth are due to rising cost inflation and binding service bottlenecks. In addition, the US policy use of an SPR release, a potential deal with Iran, extreme price volatility, and the growing risk of a recession next year reduce producers’ incentive to expand.

There are two ways of interrupting a secular bull market: i) enough demand destruction so that inventory level normalizes; ii) debottleneck supply with investments.

Financial and Physical Risks

Today, we feel the consequences of a capital-starved commodity market, with no inventory buffer against large shocks - from the Russia-Ukraine war to China's COVID wave and the most significant SPR oil release in history.

One of these consequences is what Jeff Currie from Goldman has called a volatility trap in many commodity futures markets to a sharp rise in physical inflation.

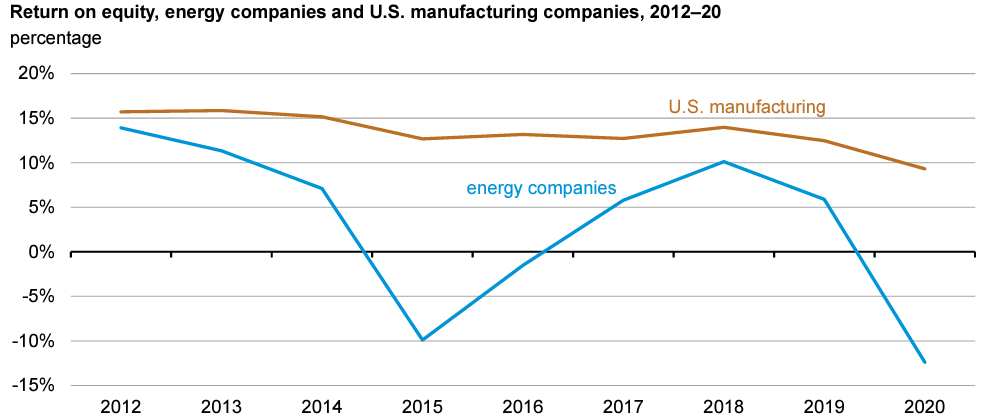

Also, now there is even the stagflation risk. Historically, the financial constraints in physical markets are driven by low returns.

Even though the O&G industry has condemned ESG exclusively, the return on equity for the energy companies has been lagging behind U.S. manufacturing companies in the past decade.

However, oil prices more than doubled in the past twelve months, driving returns upward, though the constraints are present. Hence, today's financial impediments are no longer driven by low financial returns in physical markets.

They are the cumulative effect of years of falling capacity to channel capital into the sector — managers ignoring commodities as an asset class to banks losing entire physical trade finance divisions.

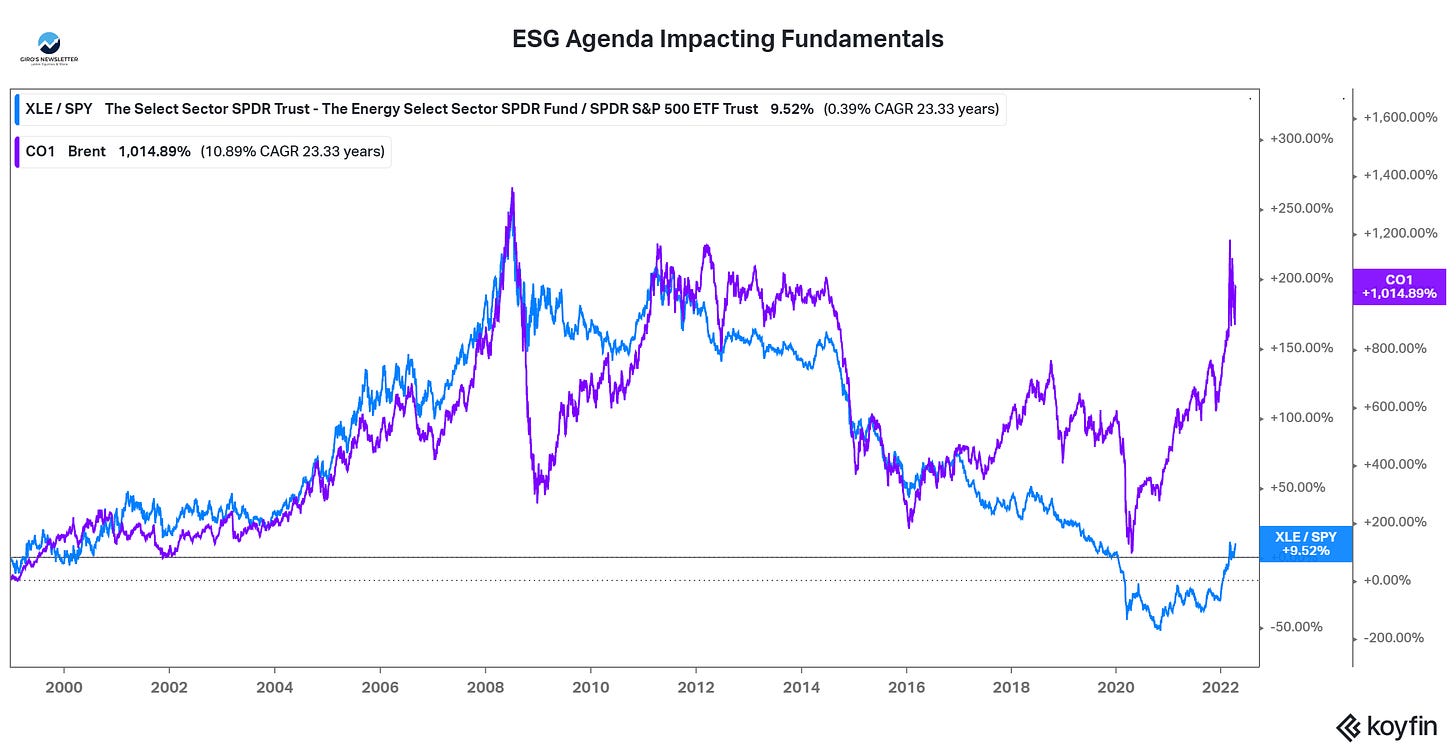

While these constraints make it look like the market is pricing the end of the supercycle, with commodity-related equities, bonds, and even futures dislocated from spot fundamentals, the reality is far more complex.

In fact, the constraints are exposing a more profound mismatch between financial and physical risk — one has only seen in the most extreme market environments.

Even if market participants remained convinced in the view, they could not place a commensurate position. While the market may be high on conviction, financial constraints make it short on position, and those who can maintain a long position likely to face outsized returns commensurate with the higher volatility.

Industry Capital Deficit

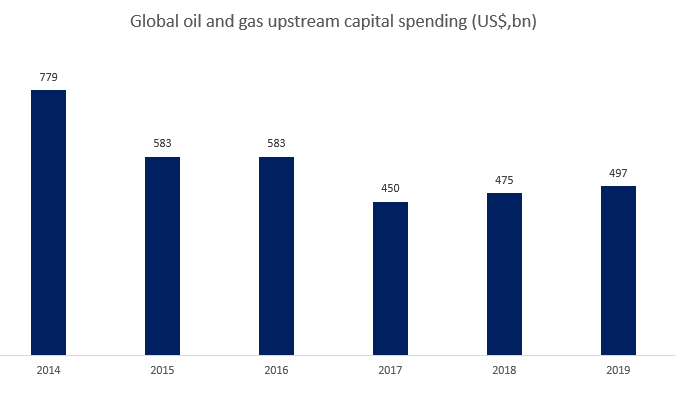

It is essential to understand how banking and environmental policy – has deepened the capital deficit facing commodities today relative to history.

These policies impact physical markets in different ways. For example, the environmental policy restricts companies’ access to equity and bond markets, lowering their ability to make long-run Capex investments.

In addition, banking regulation impacts companies' access to working capital needed for OPEX.

Indeed, the rise of ESG investing has coincided with an imbalanced climate policy program focused on lowering hydrocarbon demand with little or no focus on managing the decline in hydrocarbon supply.

Without a clear policy around hydrocarbon supply, the market has taken responsibility for restricting access to capital for hydrocarbon companies — via ESG investing — to drive the transition.

However, with energy companies facing a declining long-run demand profile, there is little incentive to grow long-run supply capacity, even though millions of jobs rely indirectly on oil.

As a result, capital restrictions and asymmetric policy have prematurely lowered the supply of hydrocarbons and forced up prices and physical inflation.

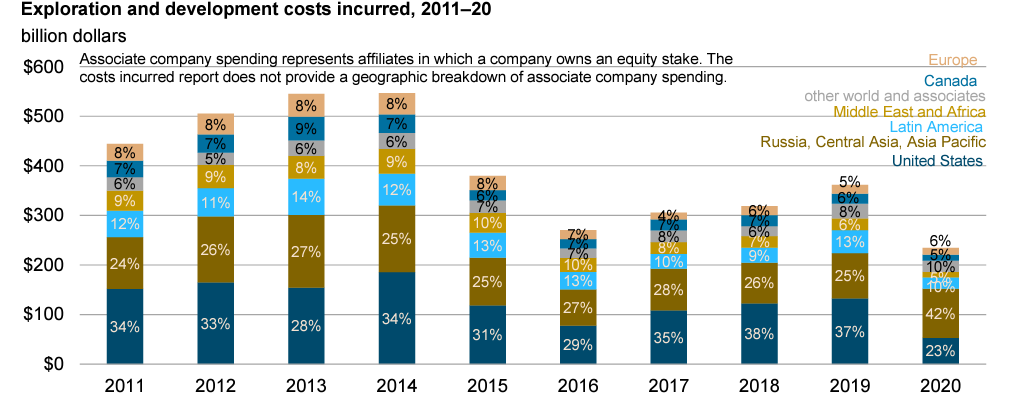

Indeed, from 2014 to 2019, the global oil and gas upstream capital spending fell 36%, and Capex commitments in long-cycle oil and gas projects have been cut by more than half, while today, physical inflation in the Eurozone years to correct.

Moreover, the market solution to this imbalance — higher returns driving capital investment — has come during a period of tightening central bank liquidity amid growing stagflation concerns.

Finally, there is also the risk of a concentration of investment in new E&P projects in different regions, leading to an energy dependence for a few areas.

For instance, from 2011 to 2020, the investment in exploration development in Europe shrank by almost half, creating a situation where the countries might rely on external supply, such as Russia.

Volatility Trap

Most concerning is that a capital deficit in commodities can become self-sustaining. A lack of risk capital lowers market participation, driving down liquidity, exacerbating volatility, and further discouraging potential lenders and investors, reinforcing lower participation.

Although public attention has been focused on the ability to grow natural supply in the current environment, the underlying shortages in storage and transportation are the primary constraints on both supply and demand growth.

The infrastructure in Oil & Gas industry is so depleted that much of the adjustment has been and will continue to be in demand. This is because demand is the quicker and lower cost margin of adjustment, not supply.

Another way to view this is that destroying demand is much faster and cheaper than building expensive pipelines with long lead times. As a result, price spikes typically lead to demand destruction, not new supply.

The demand destruction, in turn, creates dramatic price declines and, hence, the price volatility that we currently see today.

However, the much-needed investment in new infrastructure is ultimately discouraged by the increasing risky price environment in the core returns on these assets is frustrated by the much-needed investment in new infrastructure.

Also, demand destruction is not a long-term solution to the problem. Shortages will develop again once demand recovers and create subsequent pricing spikes.

This is a vicious cycle that continues to repeat itself. But not only do these infrastructure constraints restrict demand growth, but they also restrict the ability to grow supply.

This suggests that solving the fundamental supply problem will not solve the deliverability problems currently facing the O&G market.

Additional barrels from an SPR release would only provide temporary relief if fundamentals do not change. As we saw in the 1970s, such a volatility trap can create persistently higher commodity inflation and a supply-constrained market.

In the 1970s, the markets turned to long-term fixed-price contracts and built large conglomerates to deepen the balance sheets required to deal with these funding stresses.

In the 2000s, the North American LNG crisis ended with the loss of 200k manufacturing jobs due to the increase in heating demand during winter, already exhausted inventories, and a deadly $10 spike in gas prices.

The Wrong Risk

In financial markets, risk management is focused on value at risk (VaR) - the number of dollars lost in the worst 5% of outcomes across an entire portfolio.

Risk management is centered on physical units in physical markets — the price risk inherent in the barrels shipped. Yet when prices and volatility rise, so does the VaR associated with a given volume of commodities.

In extreme cases, this VaR can rise faster than banks' willingness to bare it, making it increasingly difficult for commodity trade companies to access the financing for their loans.

Moreover, banks, swap dealers, and other commodity market risk managers who help firms hedge their volumetric risk in financial markets can themselves face regulatory-mandated constraints on their ability to trade.

To permanently solve the physical risk before we face an event of permanent demand destruction (manufacturing job losses), we need investment in infrastructure.

The problem is that investing in energy infrastructure is distinctly unprofitable. A combination of regulation, taxes, and direct market intervention has made the return on capital in the energy industry a break-even proposition at best.

The paradox is that the infrastructure underinvestment is the correct outcome. Considering the poor rates of return, the best use of capital is in other industries where rates of return are higher.

As the market solution is not concerned with volatility but rather with the expected rate of return, the market fails to generate the excess capacity or reserve capacity required to lower the price volatility.

This is a conundrum that public administrations should be discussing. In my humble opinion, energy companies should be treated as utilities, especially storage and transportation.

By ensuring the long-term return to O&G projects, the market confidently invests in the long-needed supply increase to avoid new shocks.

Regardless of timing, until we face an event of demand destruction, commodities are structurally going up, even though financial risk has increased.

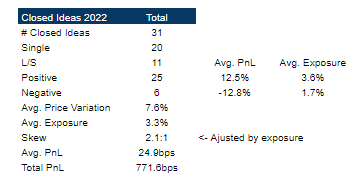

Closed Ideas

If you're a subscriber, don’t worry. I created a new section (“Trade Ideas”) to improve our communication. You can expect to receive all PRO content in your mailbox.

Also, all posts/ideas will be saved in this new section, so you can find any topic much more quickly from now on. : )