“In Dante’s Divine Comedy, the deceased sentenced to eternal searching are pushed to the deepest level of the Inferno. But for me, an eternal search across countless scientific fields beyond obvious connection managed to add up to a happy life”.

(Benoit Mandelbrot)

With the advent of globalization and improved communication technology, the economy is even more interconnected than before. Because of that, a single increase in volatility may lead to a disastrous move in the system.

In economics, the butterfly effect refers to the compounding impact of small changes. It is the idea that small things can have non-linear impacts on a complex system. The concept is imagined with a butterfly flapping its wings and causing a typhoon.

There are so many moving parts that it is nearly impossible to make an accurate prediction or to identify the cause of an inexplicable change.

In life, we may go through years — even decades — of stability followed by a sudden change caused by a series of events, causing a disproportionate impact.

Looking at traditional economic models, Benoit found that extreme volatility wasn’t supposed to happen frequently, although it did. In his opinion, economic models ignore dramatic regime changes and the existence of dramatic market shifts.

In his fractals theory, Mandelbrot’s answer to this event: “A fractal is a geometric shape that can be separated into parts, each of which is a reduced-scale version of the whole.”

“In finance, this concept is not a rootless abstraction but a theoretical reformulation of a down-to-earth bit of market folklore—namely that movements of a stock or currency all look alike when a market chart is enlarged or reduced so that it fits the same time and price scale. An observer then cannot tell which of the data concern prices that change from week to week, day to day, or hour to hour. This quality defines the charts as fractal curves and makes available many powerful tools of mathematical and computer analysis.”

(Benoit Mandelbrot)

Mandelbrot teaches us that regime changes cannot be modeled, even though analysts and economists spend their time trying to do so.

Instead, if we step back and pay attention to the more significant moving parts, we may foresee it. We can’t categorize a fractal without defining its quality.

Market agents do an extraordinary job dealing with the available evidence, which leads me to believe there is no incremental surprise from internal information.

However, models underestimate how external effects could impact the system. For instance, the market doesn’t consider the odds of a downside surprise in inflation.

Many governments, including the US, are acting to minimize the impact of higher oil prices, releasing strategic petroleum reserves, or cutting taxes.

How does it help the supply problem? It doesn’t. The alternative, then, is adjusting the market, destroying demand. Did it happen? I don’t think so.

So, why would you believe the problem is solved? I have great difficulties trying to believe that postponing a risk eliminates it. Watch out.

Today’s outline

- Cascade Effect

- Demand Destruction is Needed

- EM Will Take the Next Hit

This Week Posts

- Clash of Titans (AWS vs. Azure), June 4th, 14 pages

- STNE 1Q22: Not a Turning Point, Yet, June 3rd, 7 pages

- Brazil May Wrap-Up, Jun 2nd, 9 pages

- Double down on $XX, May 30th, 5 pages 🌟

- Food for Thought #19, May 29th, 12 pages

Premium Posts in May 🌟🔒

(Long-form only)

- MercadoLibre ($MELI) (Pinned), 29 pages

- Stone's Biggest Moat (Pinned), 14 pages

Milestone Watcher

→ 259 Pages, 30 issues, 86% Without a Paywall, 13h Channel-Check Calls in May.🔒

→ 30 Pages, 3 issues, 100% Without a Paywall, 2h Channel-Check Calls in June.

→ 1,137 Pages In 2022, 1,780+ Hours Researching, 103 Issues Published.

Cascade Effect

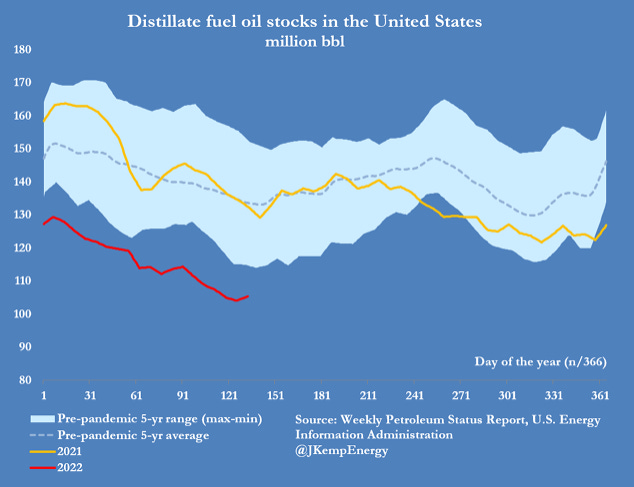

Despite the current macro risk, we see an emerging risk of a fuel crisis in the US. The diesel product inventories are nearly 10% below the five-year average, and high natural gas prices.

More importantly, the demand for diesel is relatively inelastic because it is used by intermediaries, most notably manufacturing, shipping, trucking, freight railroads, mining, and farming. The most critical is the transportation of food, though.

As a result, higher prices won’t lead to significant demand destruction, as would happen with gasoline. Distillates could pull prices to unimaginably-high levels, absent a significant economic slowdown.

We believe the oil market needs to price to demand destruction, which will drive the least elastic prices, such as those for distillate, higher.

This will likely result in higher distillate cracks versus the rest of the barrel due to the distillate’s lower price elasticity of demand and increased government interventions to reduce gasoline taxes and prices.

U.S. distillate fuel oil inventories stood at 105 million barrels last week, the lowest for the time of year since 2008. Normalized stocks are at historic lows, and the seasonally-adjusted deficit remains large and getting worse.

Demand Destruction is Needed

In our last update about crude, the market may adjust on the supply side through a storage buffer and supply elasticity; However, if that is not enough, only demand destruction could solve it.

The oil market has pivoted to a new pricing regime requiring balancing via demand destruction. However, the sole oil rebalancing mechanism lacks inventory buffers and supply elasticity.

Specifically, the global oil market remains in a deep deficit of likely 1.5 mb/d over the last 4 weeks, before the loss of Russian supply even started.

Demand destruction requires higher prices, yet this dynamic is being nullified by increased government interventions in cutting gasoline taxes, forcing the adjustment of industrial diesel demand.

However, nullifying price impact doesn’t solve the volume issue, only postponing the shock. We believe this leaves the distillate market, a term encapsulating diesel, heating oil, gas oil, and jet fuel, all similar products.

According to the head of the International Energy Agency (“IEA”), Fatih Birol, Europe could face fuel shortages this summer due to squeezed oil markets.

The crisis is bigger than the one faced in the 1970s. "Back then, it was just about oil; now we have an oil crisis, a gas crisis, and an electricity crisis simultaneously."

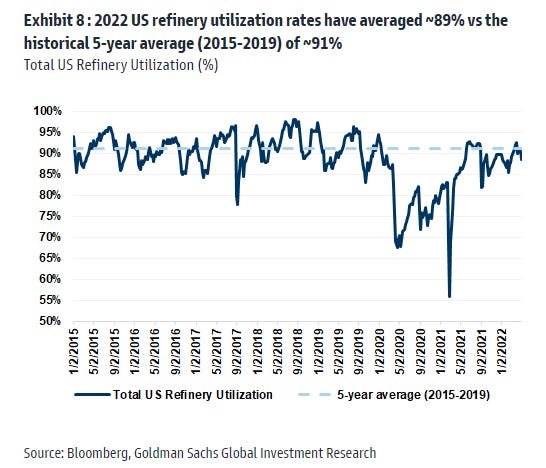

In our opinion, it’s tough to increase the diesel production as a percent of the output since each type of crude produces a different product.

Even though there is a need to increase production, we don’t see interest from refiners or available capacity for expanding production; therefore, shortages should structurally impact the chain.

EM Will Take the Next Hit

Months ago, we wrote about how the odds of a food crisis were increasing and that investors should be worried about Emerging Markets. Our thesis is evolving faster than expected, and we are warnings investors about an undertaken food crisis.

According to the Diesel Technology Forum:

“Diesel engines power about 75% of all farm equipment, transport 90% of farm products, and pump about 20% of agriculture’s irrigation water in the US. 90% of the large trucks that move agricultural commodities to railheads and warehouses are powered by a diesel engine. Diesel powers 100% of the freight locomotives and inland barge and towboat marine vessels that transport bulk harvested crops such as corn and grain to processing facilities… In the agricultural sector, there is no cost-effective substitute for diesel engines with the same combination of energy efficiency, power, and performance”.

Diesel plays a crucial impact on agriculture. But unfortunately, this fundamental reality is commonly ignored by those who do not try to understand how our world really works.

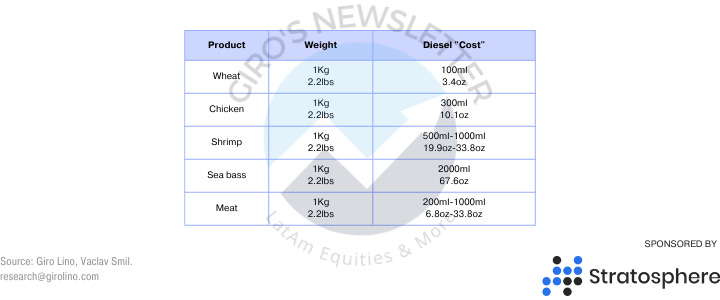

Interestingly, Vaclav Smil further estimated the diesel impact on our daily food consumption, which is a slap in the face of ignorant preaching of quick decarbonization plans for the world.

Also, Russia, a leading fertilizer exporter, could continue with export controls. So, increasing competition for key agricultural inputs in 2022 and 2023 would limit the output rises, prolonging the impact of high food prices. The upshot is without parallel.

We might be walking into a humanitarian crisis. The war in Ukraine is devastating countries like Egypt, which generally gets 85% of its grain from Ukraine, and Lebanon, which got 81% in 2020 (96% considering Russia).

A couple of weeks ago, Sri Lanka defaulted on its international debt for the first time, the first victim of surging food prices.

We believe that low and low-to-middle-income countries in Central Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and the Caucasus would be worst hit by the immediate shocks in the food commodity markets.

Many of them have food imports as a percent of the GDP above 1%(!). Also, food expenditure accounts for up to 50%(!), so the local population is vulnerable.

Even though nobody is talking about that, there is a big chance of a massive exodus in vulnerable countries, generating the largest refugee crisis.

We should add to that the already existing humanitarian crisis in Ukraine, raising an unbelievable risk for Europe. But, let us not fool ourselves; history offers a taste of how the migration process may have devasting consequences if not handled properly.

Finally, we’ll not extend today’s discussion to Europe, but we flag the rising risk in the region, with the odds of social disruption in multiple geographies increasing.