Throughout the week, we received a bunch of feedback from Pix Handbook - Part I. The best feedback we had was regarding using more images and less writing.

We take feedback as input to improve the quality. So even though the learning curve might take a while, eventually, we’ll get there.

When we decided to split the posts, Part II was 99% ready. Nevertheless, we decided to consider the previous comment and replaced a lot of paragraphs with images.

So, instead of a 15-page length, we resumed it to 10 pages, allowing a better experience and a less exhausting reading for everyone.

Today’s post is the Part II of our Pix Handbook. Since we commit to maintaining our posts between 10 and 15 pages, we will have a Part III post about Pix.

By the end, readers will have access to a complete and comprehensive handbook for understanding any instant payment and its impact on the economy and businesses.

We understand a few of you would like to access our financial impact on market participants quickly as possible. Still, we’re not in a hurry to deliver an output without collecting enough evidence to support it.

Even though our job is focused on LatAm, we believe the value of delivering a write-up that can be replicated for different countries unleashes a tremendous value for our readers.

Also, instant payment systems have proven incredibly more complex than we first estimated. So far, we have invested much more time than we first expected between research, channel checks, and crunching numbers. It’s been quite challenging, though rewarding.

Today’s outline

Pix Infrastructure

- Settlement

- Instant Payment System (SPI)

Transaction Accounts Identifiers Directory (DICT)

- Safety, fraud, and money laundering

Global FPS

- The Different Players

- Benchmarking

- Pix Outlook

Pix Infrastructure

Settlement

The settlement between different payment service providers will be done in a new centralized infrastructure called Instant Payment System (“SPI”), owned and operated by the BCB.

The system will settle transactions on a one-by-one basis as soon as they are processed. Settled transactions will be final and irrevocable.

Under Pix scope, the SPI is the infrastructure that settles transactions between different institutions through their Instant Payments Account (“PI accounts”), which are specific-purpose accounts held at the BCB by the SPI direct participants.

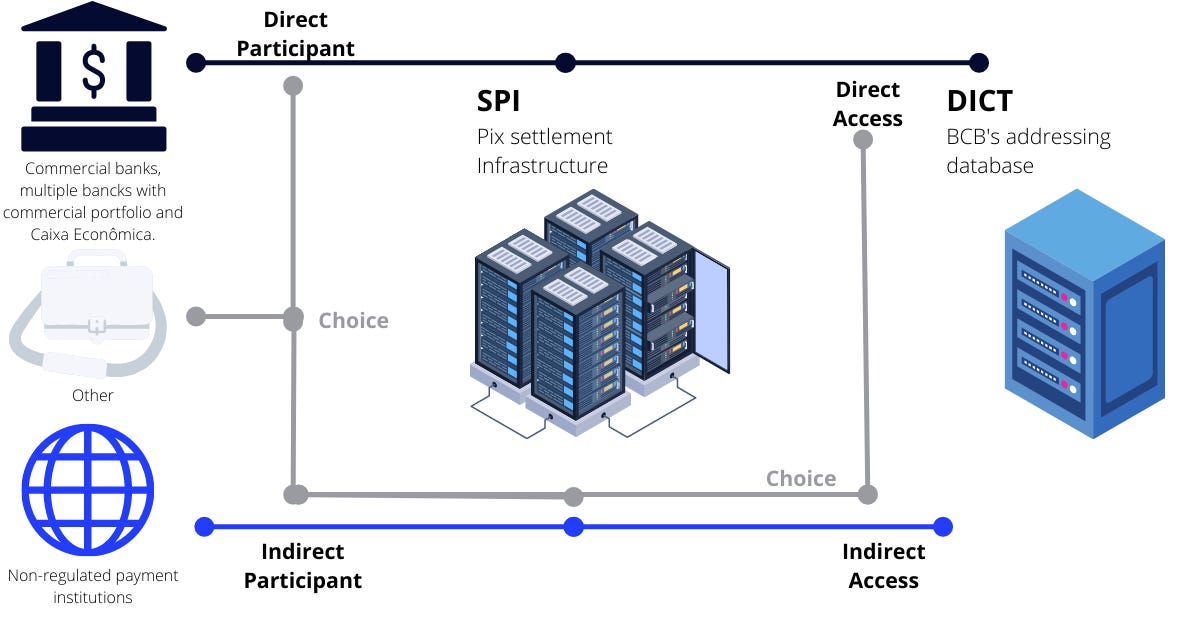

There are two types of participants in the SPI:

Direct participants — they settle Pix transactions directly in the SPI: commercial banks, multiple banks with a commercial portfolio, and saving banks that are Pix participants must be direct SPI participants.

The other institutions authorized to operate by BCB participating in Pix may choose to be direct or indirect participants in the SPI.

Indirect participants – their Pix transactions are settled through a direct participant or a special settlement agent. Payment institutions not regulated by BCB participants in Pix must necessarily be indirect participants in SPI.

Instant Payment System (SPI)

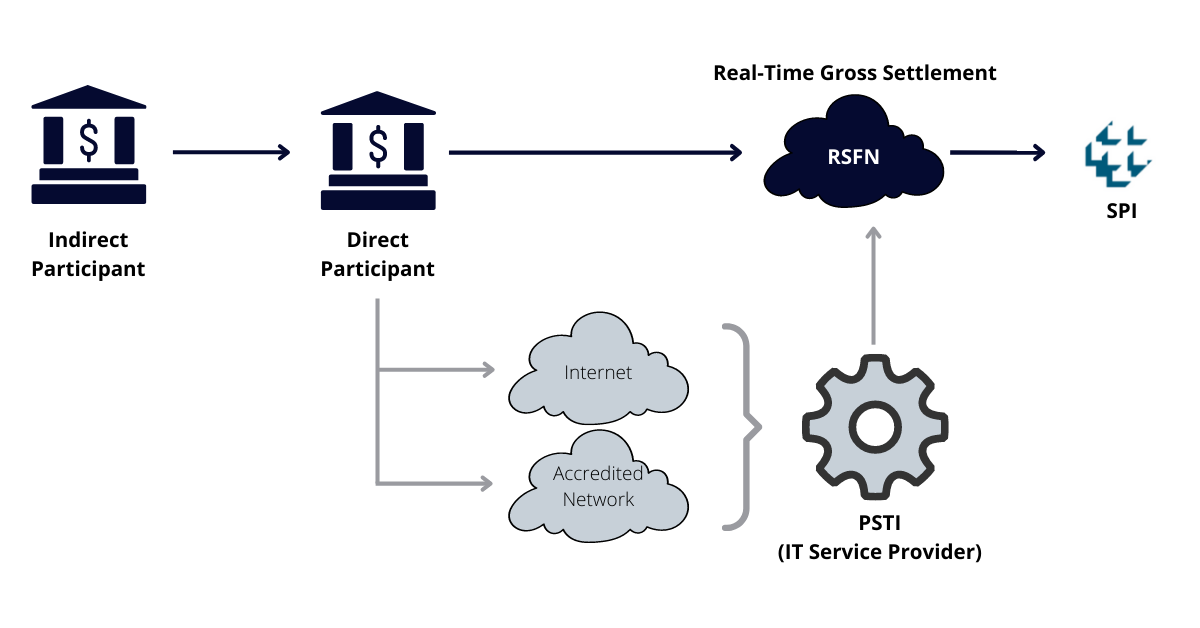

The Instant Payment System (“SPI”) is the only centralized infrastructure for instant payments settlement between different payment service providers in Brazi, launched in Nov 2020.

The SPI is a Real-Time Gross Settlement (“RTGS”) system, which means transactions are settled as soon as they are processed on a one-to-one basis. Once settled, transactions are final and irrevocable.

The instant payments (Pix transactions) are settled in specific purpose accounts held at the BCB by the direct participants of the system.

No overdraft is allowed to safeguard the system’s resilience, which means the account cannot have a negative balance to perform a Pix transaction.

However, it is not possible to operate Pix without an Internet connection. Although the encrypted connection is via dedicated lines provided by certificated telecom operators, the SPI still requires internet to connect to IT, service providers. The BCB plans an offline Pix, but there is no deadline for the new feature.

Transaction Accounts Identifiers Directory (DICT)

The Transaction Accounts Identifiers Directory (“DICT”) is the Pix component — managed and operated by BCB — that stores Pix aliases linked to end users’ information and their respective transaction accounts.

The registration of Pix aliases in DICT must be requested by the Pix participant, on-demand from their respective end-users.

In addition to facilitating the payment transactions by the payer, DICT’s platform helps participants mitigate fraud risk.

Pix participants must access DICT directly if they are direct participants of SPI. Institutions that BCB does not authorize must access DICT indirectly. Indirect access to DICT requires a contract with a Pix participant with direct access to DICT.

While in most wire transfers (e.g., TED and DOC), the payer has to enter the complete recipient’s transaction account information. In Pix, the payer needs only to provide the alias for the beneficiary’s account information.

Recently, the media has raised questions regarding Pix security with recent scams and frauds. Pix has protection mechanisms that prevent scans of personal information and “fraud markers in its DICT database.”

In the event of suspected fraud or consummated fraud, the transaction (and the scammer) is marked as “fraud,” and participants are warned.

Also, institutions may establish maximum limits for transactions based on the profile of each customer, period, account ownership, service channel, and initiation procedure.

Such limits are anchored in the limits established for other payment instruments, such as TED and debit card.

Users can also adjust the limits in the app itself, and the request to reduce the limit must be accepted immediately by the institutions.

Nubank, for instance, set a low limit for Pix transactions between 8 p.m. and 6 a.m., allowing users to change it only for the following day, minimizing the risk.

Global FPS

The Different Players

Now that we have introduced Pix and its features, we can formally compare it to different Fast Payment Systems (“FPS”).

An FSP is a system in which the transmission of the payment message and the availability of the final funds to the payee occur in real-time or near real-time on a 24/7 basis.

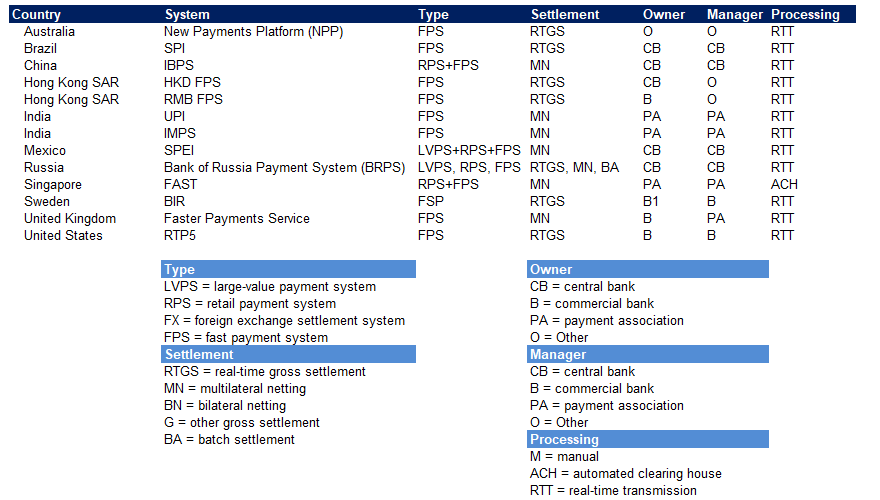

Putting all the information we commented on before, a transaction is composed of system, type, settlement, owner, and manager for a specific processing format.

While its availability could vary between open to new participants or restricted, most FPS are considered centralized structures.

Nevertheless, the Australian NPP is considered a decentralized structure. Even though the settlement service is centralized, there is a decentralized switching and addressing service.

In conjunction with the development of the NPP, the Reserve Bank (Australia Central Bank) developed new infrastructure, the Fast Settlement Service (FSS), which provides for the settlement of NPP transactions across their Exchange Settlement Accounts (ESAs) at the Reserve Bank — the infrastructure is like a domestic SWIFT network.

While closed-loop systems can also be near real-time and available 24/7, FPSs are payment infrastructure that facilitates payments between account holders at multiple payment service providers (“PSP”) rather than just between the customers of the same PSP.

Benchmarking

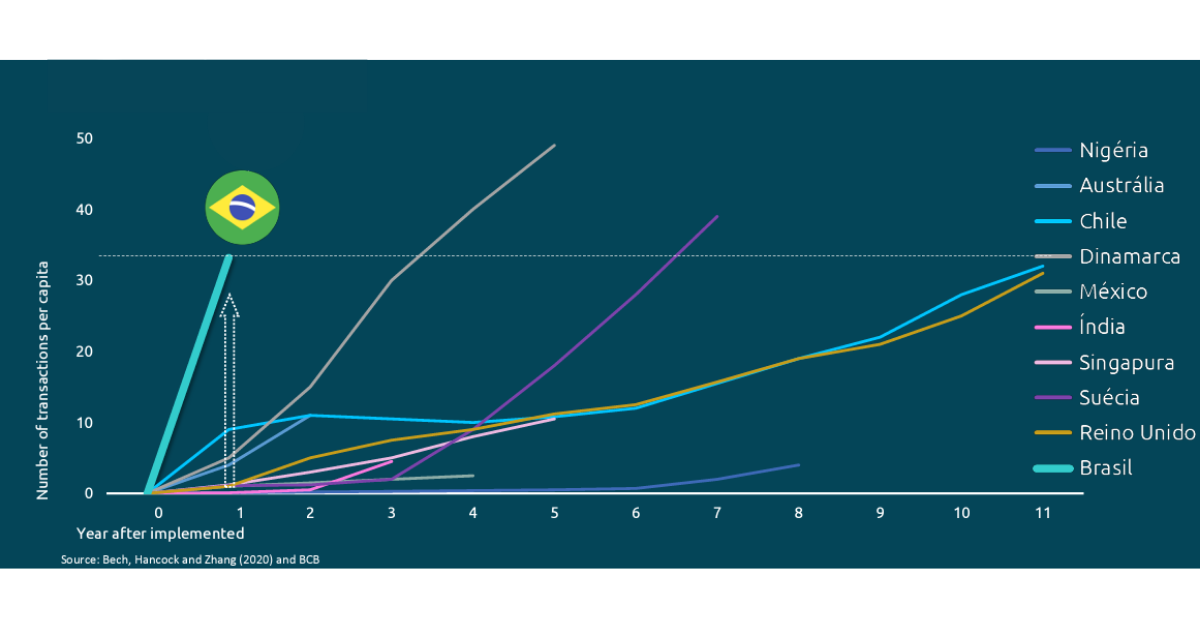

Currently, +50 countries have FPSs, and this number is projected to rise soon. While the adoption speed is reasonably similar to that of wholesale real-time gross settlement (“RTGS”) systems, early adopters are predominantly emerging markets rather than developed economies.

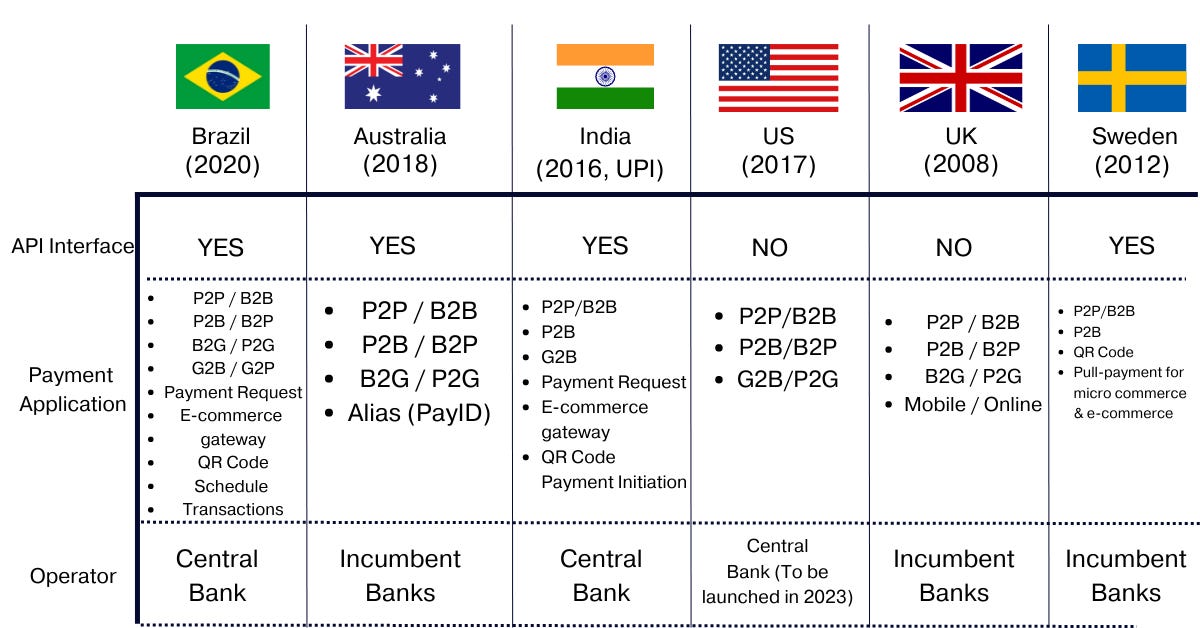

Instant payments are in different stages of maturation across the world. Our studies mapped different experiences from two to twelve years of experience rolling out an FPS.

P2P - Peer-to-Peer; P2B - Peer-to-Business; P2G - Peer-to-Government; B2P - Business-to-Peer; B2B - Business-to-Business; B2G - Business-to-Government; G2P - Government-to-Peer; G2B - Government-to-Business

So far, instant payments in Australia, India, and Sweden are the systems that have added more value to existing P2P platforms among benchmarked countries. Also, we identified a few factors that may be related to the FPS's success.

First, for all existing FPSs, their success is mainly related to the prior level of maturity of P2P before FPS. For instance, in the UK, the previous system offered many POS terminals, high credit share, high use of contactless (NFT, BT, QR), and medium-cost for merchants.

On the other hand, India had a shallow maturity level of P2P transactions before FPS, offering low levels of convenience regarding initiation time and limits, the cost for parties, and e-wallets usage.

Therefore, the FPS has incredibly more significant value-added for India than for the UK, though the acceptance curve for UPI seems to lag in different systems.

Second, an FPS's success cannot be measured by its overall penetration. For instance, UPI is more relevant to P2B transactions than P2P.

So, the number of transactions per capita is not relevant, though its representative in the personal consumption expenditure (“PCE”) is far greater than any other system.

According to BIS, a year before UPI was launched, the digital payments as a percentage of PCE in India were ~8%, vs. 30% in Brazil, while the portion of the GDP was 5%.

According to the last data released, UPI represents almost half of digital payments in India, which is far superior to any other FPS.

Finally, analyzing the available evidence, instant payments still represent a relatively low percentage of overall transactions despite rapid growth, affecting:

- Credit transfer: Regulation of cost/process improvement driving banks to shift payments and push IP platform.

- Decelerating cards: High penetration and mobile adoption create additional transactions. It’s worth highlighting that percentual growth is impacted only because of total transactions with the IP.

However, the available evidence suggests that the pace of card transactions accelerates if we exclude IP, meaning that the archetype is a front door product that stimulates the consumption of new products. - Replacing cash: a cash-intensive market with high mobile adoption driving direct replacement.

Pix Outlook

Estimating a scenario for Pix for the following 3-5 years is not an easy task. Even though India looks like a good benchmark, we have our concerns.

It took India’s UPI 4 years to reach 2% of PCE, considering both P2P and P2B transactions and a much weaker card payment infrastructure compared to Brazil, as previously commented.

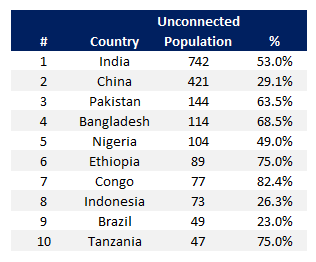

Although IP has dramatically improved financial inclusion, utilization of the platform is higher among already banked segments. Also, other than the prior system to the IP, there is a second layer regarding lower internet penetration.

According to Kepios, in 2021, 62.5% of the world population had access to the internet, versus 47% in India and 77% in Brazil. Also, according to The Inclusive Internet Index 2021, affordability is the main reason for the non-adoption of the internet in India.

Also, in absolute terms, India is the country with the largest unconnected population globally, with over 740 million people unconnected.

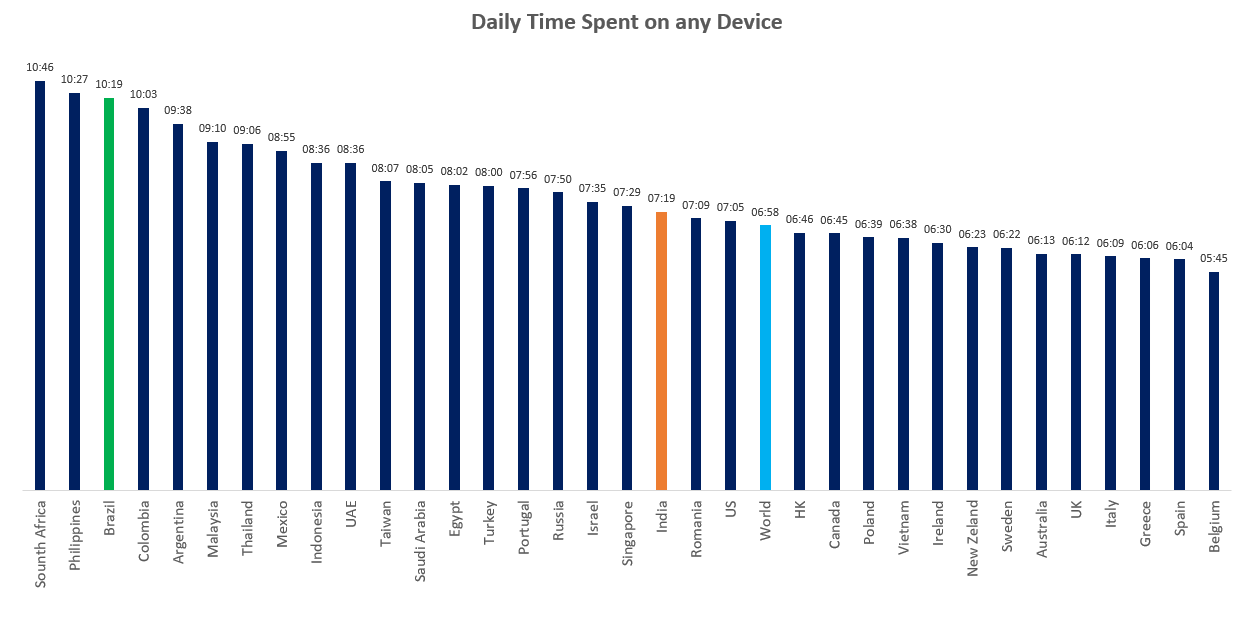

However, as UPI proved to succeed in India, we had to consider that different factors affect its adoption, such as daily time spent using the internet.

According to GWI, the world’s daily time spent on any device is 6m58s. Meanwhile, the average daily time spent on any device in India is 7m19s, and in Brazil, 10m19s.

Also, as mentioned before, UPI benefited from various peculiarities in the Indian payments ecosystem not present in Brazil, including a limited culture of card payments before the launch of the platform and a high degree of government intervention.

In Brazil, we believe that Pix adoption is steeper because the country has similar characteristics to most emerging markets, in which digital payments had a low penetration on the overall PCE. At the same time, cash and wire transfers were the dominant systems in fund transactions for P2P.

On the other hand, unlike most emerging markets, Brazil had top-notch regulations and product offerings among digital options.

Therefore, we believe that Pix should deliver superior results than most peers. As a best-case scenario, we expect PIX expenditures could reach R$220 billion in 2026, up to 2.5% of PCE.

In other words, PIX volume could be equivalent to 7-11% of debit card expenditure, a rather generous assumption, in our view.

Our expectations would make PIX far more successful than CoDi in Mexico and on par with the NPP in Australia, implying fewer benefits than in India.

Finally, in the next week, we'll present our estimates for Pix impacts on P2B, P2P, and B2B transactions and the long-term impact on industry participants.